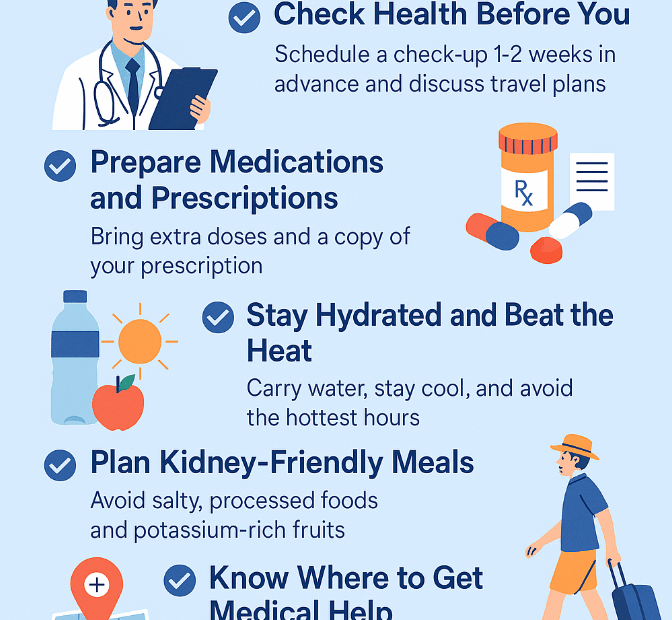

🌞 How to Prepare for Summer Travel with Kidney Disease – 7 Essential Tips

✈️ Yes, You Can Travel with Kidney Disease! Summer is a time for rest and relaxation, and kidney disease doesn’t mean you have to give up travel. Whether you have chronic kidney disease (CKD), are… 🌞 How to Prepare for Summer Travel with Kidney Disease – 7 Essential Tips