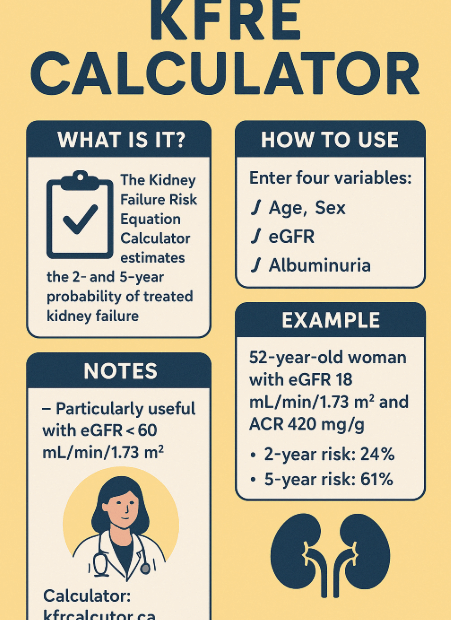

Predicting the prognosis of Chronic Kidney Disease with KFRE:

Why Is KFRE Gaining Attention? Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) is often a “silent” condition. Many patients don’t feel symptoms until their kidneys have deteriorated severely, leading to the sudden need for dialysis.However, a tool developed… Predicting the prognosis of Chronic Kidney Disease with KFRE: