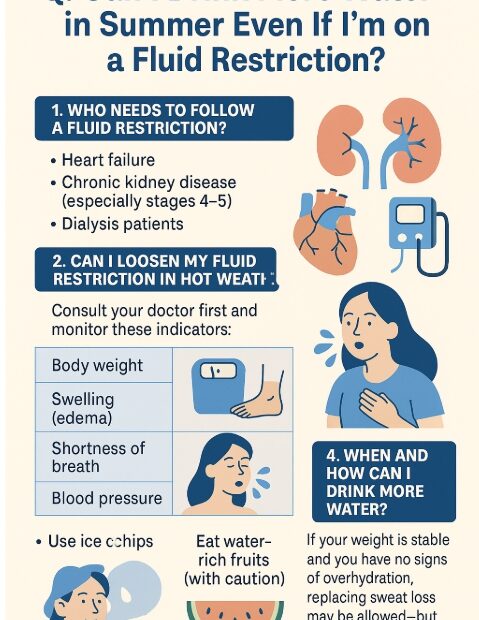

Q. It’s summer and I’m sweating a lot—can I drink more water even though I’m on a fluid restriction?

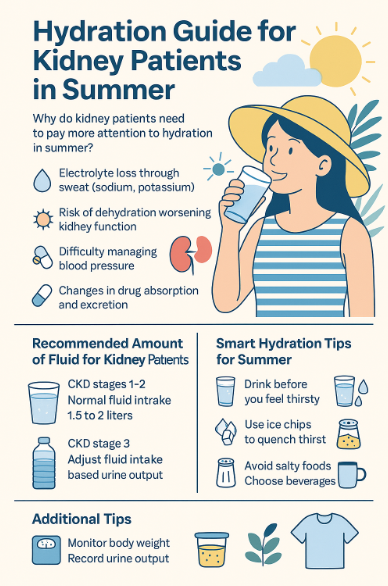

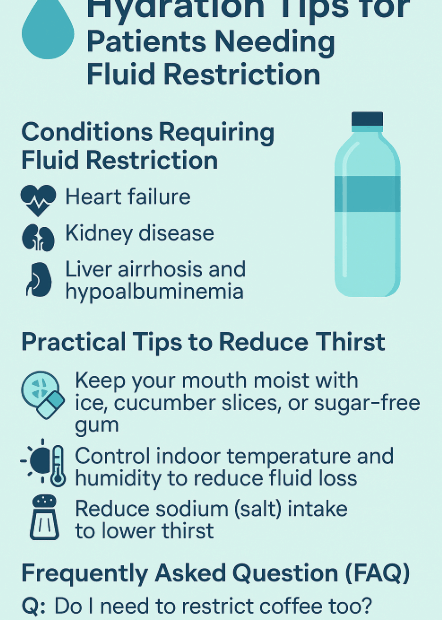

During hot summer months, we sweat more and naturally feel thirstier. But if you’ve been told to restrict fluids due to chronic kidney disease (CKD), heart failure, or dialysis, you might be wondering: “Is it… Q. It’s summer and I’m sweating a lot—can I drink more water even though I’m on a fluid restriction?